Life of Pi - The Story You Choose

Imagine this: At the end of a Harry Potter film our hero lies in a muggles hospital, interrogated by officials who must make a report about what actually happened to him. First he relays the wondrous events the film just depicted — full of wizardry, outlandish characters, loyal friends, and the arch-enemy Voldemort — featuring Harry as the hero and the chosen one. But the officials find it impossible to accept this fantastical story as real; they ask for something more plausible. Harry agrees and tells them an alternate story: He was orphaned, lived on the streets of London, cold and half-starved, and barely survived abuse and privations in his lonely struggle to stay alive. This second story is grisly enough that the officials can only exchange disturbed glances. Finally Harry asks: "Which story do you prefer?" On the one hand, the glorious tale that has enriched and inspired much of the planet in the best-selling book series of all time; on the other, a painful but literally accurate account of solitary and unredeemed suffering.

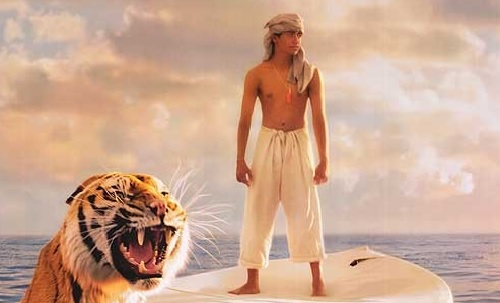

The same choice is presented near the end of Life of Pi, the remarkable film Ang Lee has made based on Yann Martel’s prizewinning novel. Pi tells two stories about being stranded on the ocean for over 200 days, one that occupies nearly the entire film, full of beauty and wonder, struggle and triumph, as breathtaking and miraculous in its way as a Harry Potter tale. Then, at the behest of officials, he tells, very briefly, a second story — terrible, heart-wrenching, unbearably harsh, without redeeming qualities, but sadly much more plausible than the first. "Which story do you prefer?" he asks.

Both stories are about survival against all odds. Only one, however, contains elements that excite our imagination and inspire our awe. Pi does not ask his listeners which story they think is true, or which one they think really happened. He asks which one they prefer. The stories we prefer become the stories we remember, the ones we retell, the ones that last; the greatest of them satisfy the mind and heart for generations or millennia.

Barack Obama sent Yann Martel a fan letter praising his book as "an elegant proof of God." It seems quite different to me. Life of Pi is an eloquent example, and it is explicitly presented as such, of the way our imagination weaves wondrous stories to redeem a reality that could otherwise be too painful to accept. Not a proof of God so much as a proof of the human imagination’s unbridled ability to envision him or what his world might be like if he did exist.

As the holidays approach now, Christians everywhere recount the miraculous stories that were told and passed down about a visionary Jewish teacher who was crushed by the iron fist of the Roman Empire — stories that redeemed not just that single life but that of untold millions for two thousand years. The "stories we prefer" infuse otherworldly significance into the limits and disappointments of even the most tragic of lives.

Life of Pi, with its astonishing visual beauty and its stirring challenges and triumphs, is a powerful, self-referential illustration of the indomitable story-making urge, the life-giving source of all our greatest myths.