A Stay in India (7): Astonishing Beauty in Surprising Places

We walk the winding steps and pathways that run between the houses, stone courtyards and cowsheds that are clustered here at the edge of the mountain in Joshimath. The whole town is built on steep cliffs. Corn, red chilies and yellow squash grow in every available space. On the slate and concrete roofs, on the stones of the family courtyards, even in the branches of trees, chilies and grain and grass for the cows are set out to dry in the sun. Women slap cow patties against stone walls where they will hang until dry enough to serve as winter fuel. Children play badminton on concrete patios atop the houses, or in the streets, for there are no other flat places for games in these mountains.

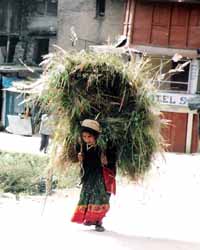

Most every family keeps at least one cow in this dense cluster of homes. Families share rustic latrines. Steps lead up to the roofs, where the laundry is hung and dogs sprawl to sleep in the afternoon. Women handle all the domestic work, starting before sunrise. Cutting grass for the cows on the steep slopes, they carry back up the mountain huge bundles that dwarf their feminine frames, bent low under the load in their vibrant saris. Women sweep the roofs and patios and walkways with handmade brooms, wash dishes and clothing on the stones of the courtyards, tend to the animals, carry their babies, pound grain into flour. Men are nonexistent in the visible domestic scene, appearing only to run the tiny shops in the market, to work on the roads, to sit for a smoke or a game of cards.

It is heart-rending to see slightly built, beautiful women, their exquisite saris drenched in sweat, wielding pickaxes, working on road crews along with men. Much of the gravel used for roadwork and construction is created by crews of people (men, women, even children) methodically breaking large rocks into tiny ones, one at a time, with hammers. What would be accomplished in the U.S. with a huge machine in a few moments takes a group of hand laborers days or weeks.

From my window, I watch a family come to life below me in the early morning. Three children run out from their sleeping rooms to a corner of their slate courtyard. The girls squat and the boy stands as together they relieve themselves before running into another low building for their breakfast. Later, one of the girls washes dishes in the same corner of the courtyard, and in the afternoon the mother comes to dry grain there, as two cows eat the grass she has laid out for them, also on this patio — the central stage of so much of their domestic life.

In the outskirts of towns and cities sprout row upon row of tiny "shops" of concrete or wood, perhaps 8 feet wide, with metal rollup doors that can be closed at night like locking self-storage cubicles. There is an endless redundancy of shops, dozens of which offer apparently identical goods all within sight of one another. Some, plying engine repair or welding or brake work, are black and grimy. Most others are cluttered and ramshackle. Each has a proprietor sitting or napping inside, with others squatting or lying on cord cots in front. Each sells cellophane packets of "pan", a betel-leaf derivative that is an addictive stimulant and turns teeth and gums bright red. Stray dogs are everywhere, all looking like the close blood relatives they in fact all are, some sleeping with legs sprawling into the traffic lanes. Cows wander at will; water buffalos are driven on by their masters. Expertly painted Coca-Cola signs blaze in red and white from every flat surface.

Move from the outskirts toward the center of an old city, and the traffic becomes ludicrous. Cycle rickshaws, auto rickshaws, bleating motor scooters, and men hauling burlap sacks piled eight feet high on bicycle-driven carts, weave in and out of an incessant stream of honking taxis, private cars and trucks, all of them dodging pedestrians and cows and water buffalo and dogs, unperturbed — incredibly — by the rushing traffic that passes within inches of their bodies. In stark contrast to this chaos, the dust and the fumes, and the grimy storefront cubicles along the road, are the schoolchildren in starched, clean uniforms, the girls with crisp and spotless white scarves over blue punjabis, the boys in white shirts, ties and short pants. The children, always with heavy backpacks of homework, walk the roadside or cram twelve at a time into auto rickshaws, designed to hold five, that serve as school buses in the early afternoon. I wonder how such perfectly attired, beatific children could emerge from the dingy pandemonium of the city, and from the dark and worn-out men in the stalls along the road who must, after all, be their fathers. Yet the women of India are beautiful, radiant, as if from another world; it must be they who account for these lovely children.